Musée de Cluny in Paris is the French Musée National du Moyen Age and has an impressive permanent collection as well as holding frequent temporary exhibitions. The current exhibition displays the range of artistic production from the reign of Charles VII, with paintings, sculptures, stained glass, tapestries and illuminated manuscripts. It also has a section devoted to the works of Jean Fouquet, one of the most renowned French artists of the fifteenth century.

Charles II came to the throne in 1422, a time of political instability, with the Hundred Years War continuing and the Armagnacs, supporters of the House of Valois, and the Burgundians fighting a civil war. However, by the end of his reign in 1461, the Hundred Years War was over (with the aid of Jeanne d’Arc), as were English claims to the French throne. The period also saw a change in artistic production, with a new style, influenced by both Flemish realism (‘ars nova’) and the Italian Renaissance, taking over from International Gothic.

Jean Fouquet ‘Charles VII’ (c.1450 – 55)

‘Canopy for throne of Charles VII’ (1450)

Maître de Dreux-Budé (André d’Ypres) ‘Crucifixion triptych’ central panel (c.1450)

‘Crucifixion triptych’ side panels. ‘Kiss of Judas’ (left) ‘Resurrection’ (right)

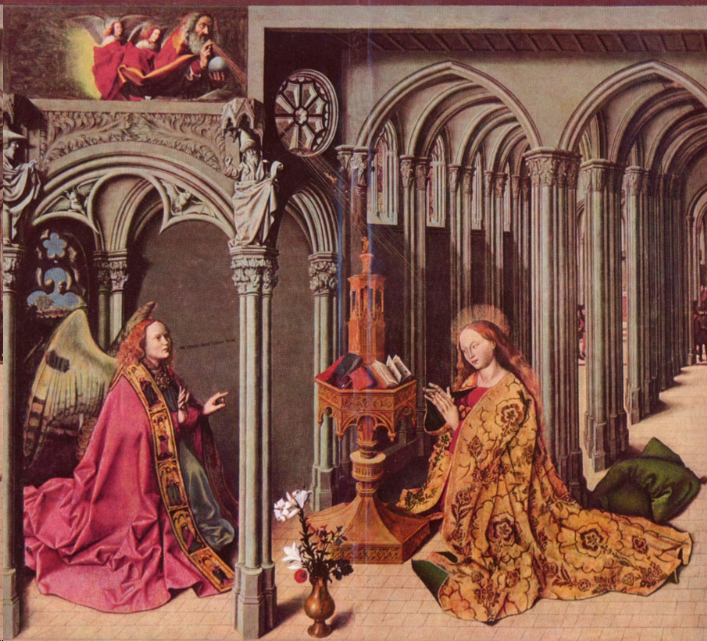

Berthélemy d’Eyck ‘Altarpiece of the Annunciation’ (1443 – 44)

‘Pietà de Tarascon’ (Provence, fifteenth century)

‘Chess Players’ (fifteenth century)

Master of Rohan ‘Grandes Heures de Rohan (1430 – 35)

Enguerrand Quarton ‘Missal of Jean des Martins’ (1466)

It was also an opportunity to see some of the remarkable exhibits that make up the museum’s permanent collection.

‘À mon seul désir’ (The Lady and the Unicorn tapestry) (c.1500)

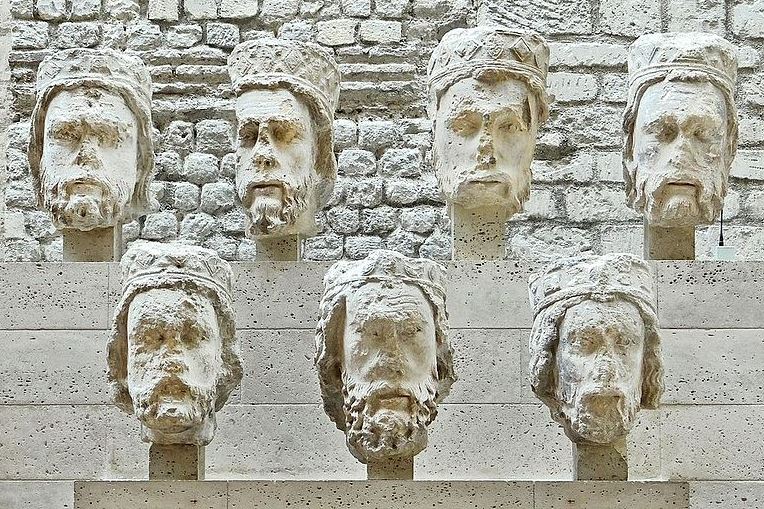

‘Heads of Kings of Judah’ (west façade Notre-Dame cathedral) (thirteenth century)

Altar frontal from Basel Cathedral (first half eleventh century)

‘Virgin and Child’ (Paris,1240 – 50)

Angelo di Nalduccio, attrib. ‘Bust Reliquary of Saint Mabilia’ (c.1370 – 80)

‘Reliquary of Saint Thomas Becket’ (c.1190 – 1200)