Fondation Bemberg in Toulouse has one of the world’s largest collections of works by French artist Pierre Bonnard (1867 – 1947).

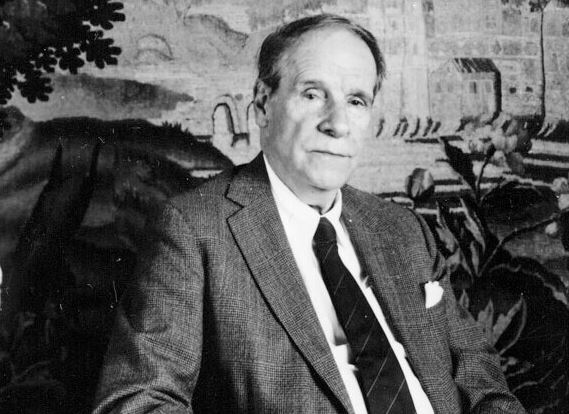

Pierre Bonnard

Pierre Bonnard was born in Fontenay-aux-Roses, Hauts-de-Seine, in 1867, the son of a senior official in the French Ministry of War. Although he showed an early talent for art, to satisfy his father he studied law and and began practicing as a lawyer in 1888. However, whilst studying he also attended art classes at the Académie Julian in Paris, where he met fellow artists Paul Sérusier, Maurice Denis, Paul Ranson and Gabriel Ibels. In 1888, Bonnard was accepted by the Ecole des Beaux Arts and there he met Edouard Vuillard and Ker Xavier Roussel. From 1893 Bonnard lived with Marthe de Mèligny who had been his model. They married in 1925 and remained together until her death in 1942.

In 1888, Bonnard joined with his friends from the Académie Julian to form Les Nabis. Although as artists they had very different styles they did have common artistic ambitions. In October 1888 Paul Sérusier travelled to Pont-Aven in Brittany where he met Paul Gauguin. Under Gauguin’s guidance he painted ‘The Bois d’Amour at Pont Aven’, known as ‘The Talisman’, using patches of pure colour. On his return to Paris, Sérusier showed the painting to his Nabis colleagues, including Bonnard, and this was to influence their future styles.

In 1891, Bonnard met Toulouse-Lautrec and in December of that year he showed his work at the annual exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants. He also continued to display his work with other members of Les Nabis.

In 1893, he saw a major exposition of Japanese graphic art at the Durand-Ruel Gallery, and the Japanese influence began to appear in his work. Because of his passion for Japanese art, his nickname among the Nabis became ‘Le Nabi le trés japonard”. However, In 1894, he turned in a new direction and made a series of paintings of scenes of the life of Paris.

Into the twentieth century, Bonnard continued to refine his painting style and also diversified into illustrations for books and literary magazines such as ‘La Revue blanche’, as well as decorative panels. The outbreak of World War II forced Bonnard to leave Paris for the south of France, where he remained until the end of the war. In 1947 he finished his last painting, ‘The Almond Tree in Blossom’, a week before his death in his cottage on La Route de Serra Capeou, near Le Cannet, on the French Riviera.

Pierre Bonnard ‘L’omnibus Panthéon-Courcelles’ (c.1890)

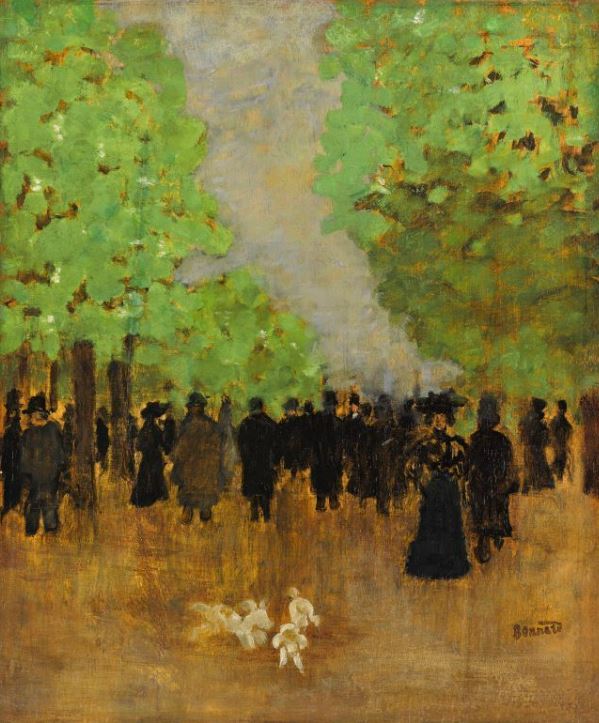

Pierre Bonnard ‘Tuileries (Scène de rue)’ (1894)

Pierre Bonnard ‘Au café’ (c.1900)

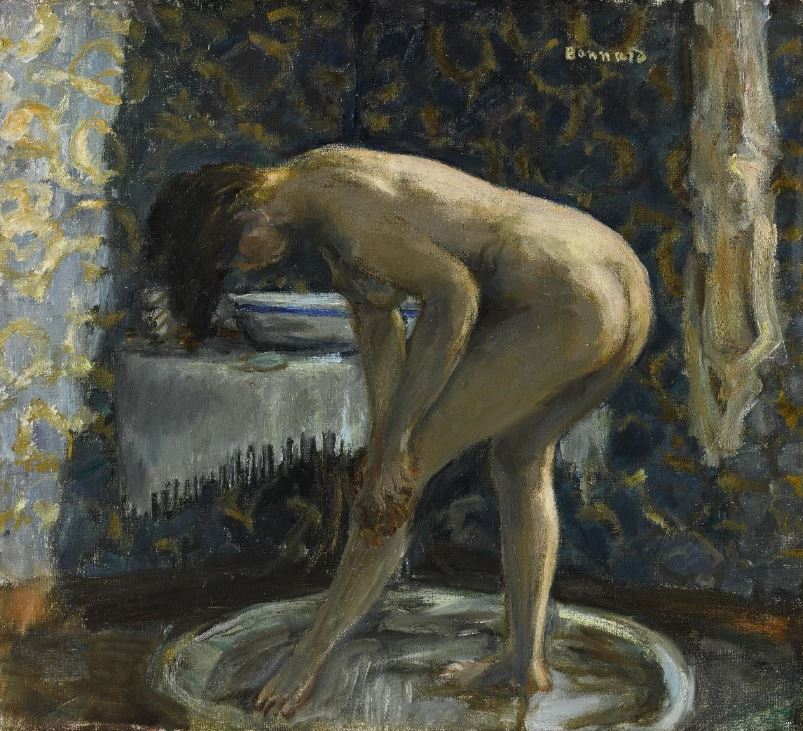

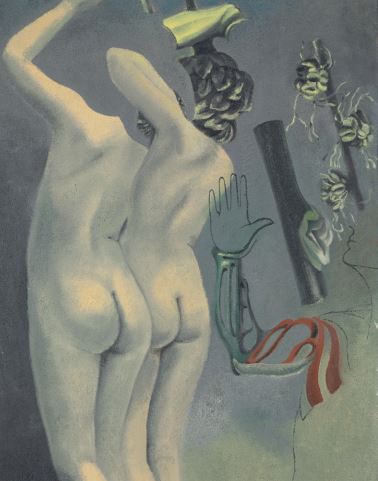

Pierre Bonnard ‘Nu au tub’ (1903)

Pierre Bonnard ‘Interior’ (c.1905)

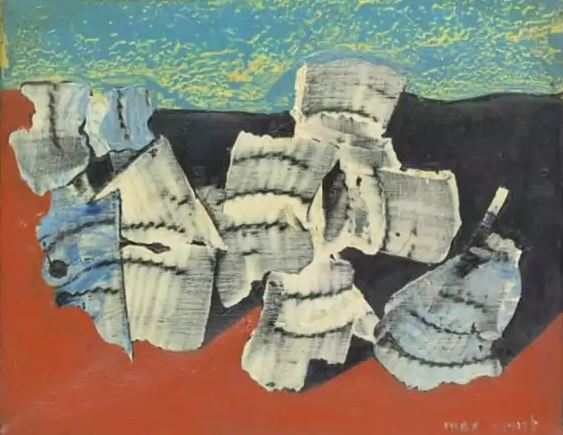

Pierre Bonnard ‘Voiles au sec ou Les voiliers à Cannes’ (1914)

Pierre Bonnard ‘Iris et lilas’ (1920)

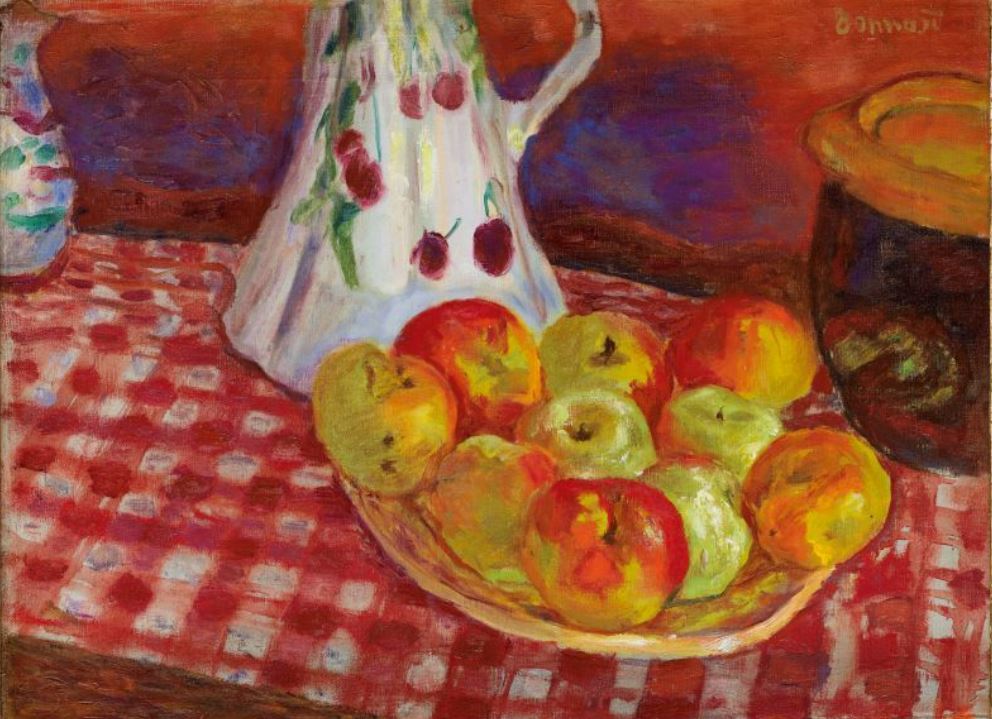

Pierre Bonnard ‘Les pommes jaunes et rouges’ (1920)

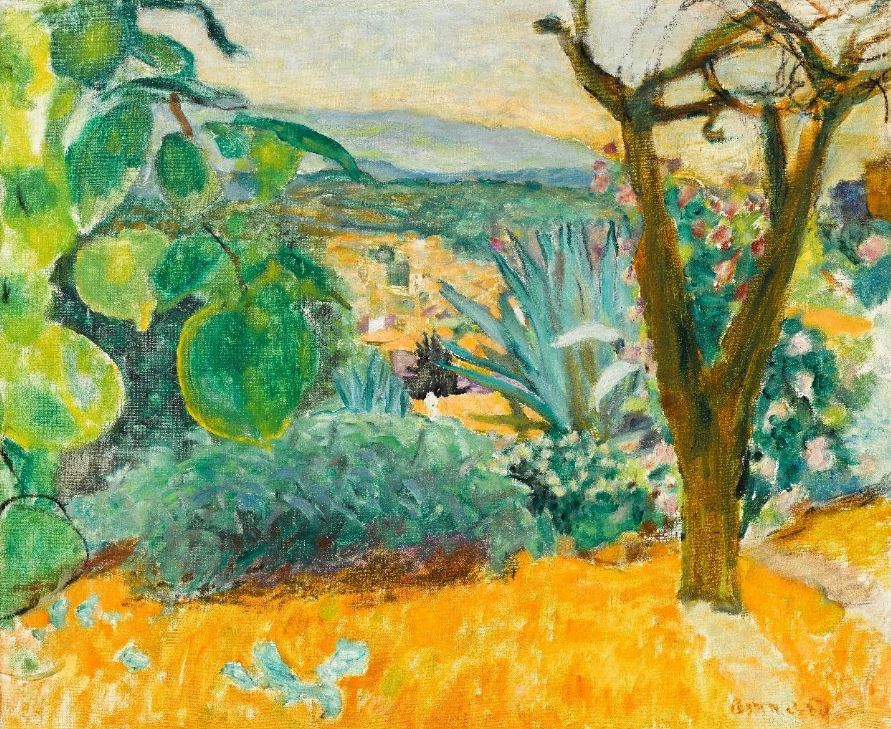

Pierre Bonnard ‘Le Cannet’ (1930)

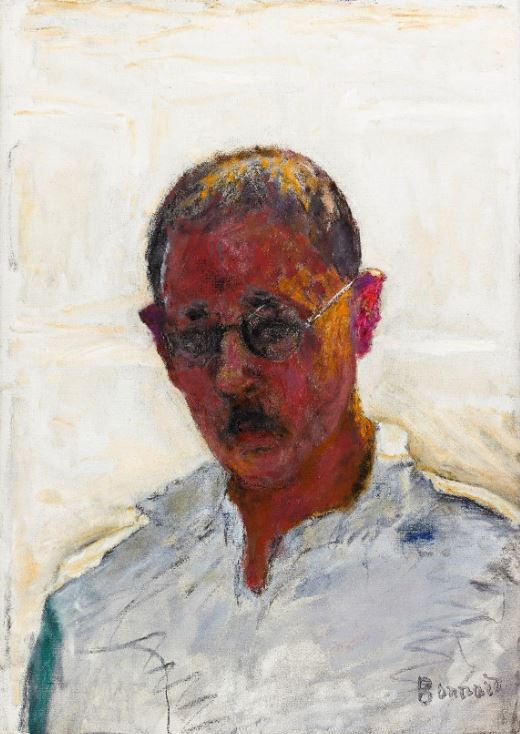

Pierre Bonnard ‘Autoportrait sur fond blanc, chemise col ouvert’ (c.1933)