At the Musée d’Orsay for this exhibition which displays the works that van Gogh produced during the last two months of his life. He spent May to July 1890 in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise, north of Paris, and there produced some of his finest works – seventy-four paintings and over fifty drawings, a remarkable output in such a short period of time.

Vincent van Gogh arrived in Auvers-sur-Oise on 20 May 1890, after having spent a year in the psychiatric hospital of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in the south of France. In Auvers he hoped that he would be able to find some kind of normality in new surroundings closer to his brother Theo. Theo arranged for a doctor in the town, Paul Gachet, who had been recommended by Camille Pissarro, to provide support for him.

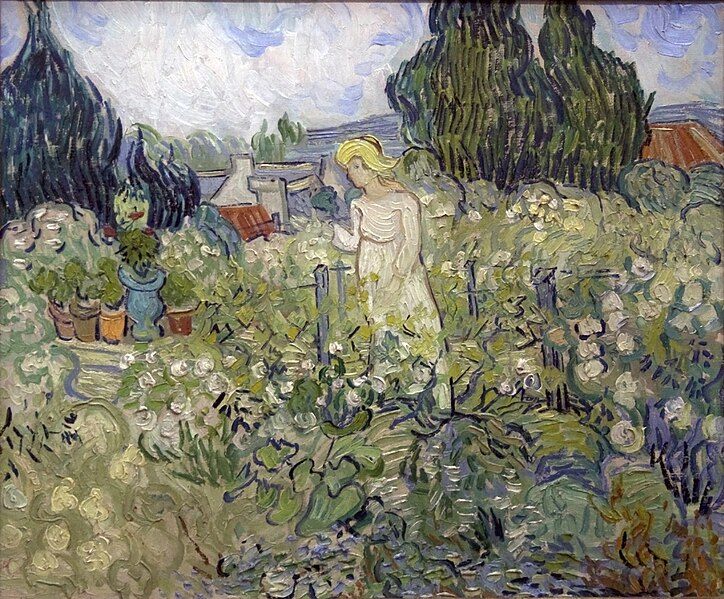

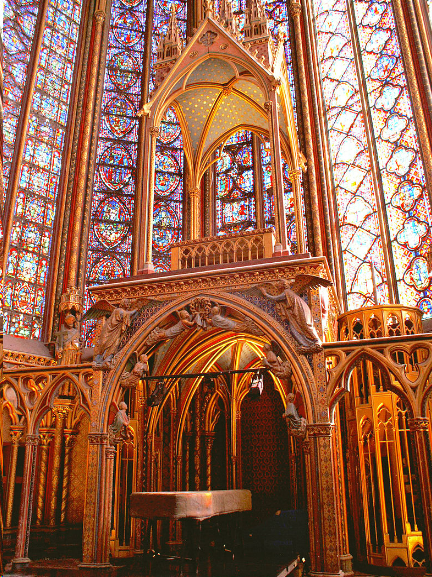

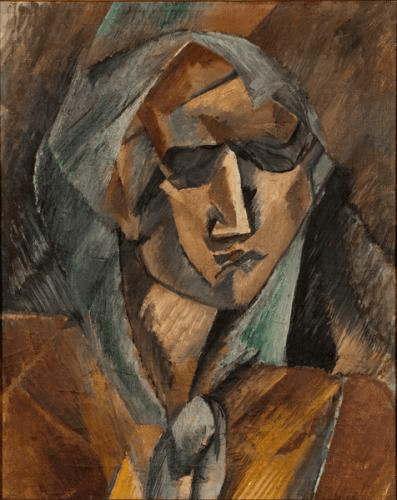

Van Gogh immediately found Auvers to be “decidedly very beautiful”, although he was extremely concerned about his financial situation and continued to see himself as a failure. Nevertheless, financial aid from Theo reassured him and with Doctor Gachet’s support he began to paint, initially views of the surrounding countryside and its cottages and portraits of the doctor and his daughter Marguerite.

Vincent van Gogh ‘Thatched Cottages’ (1890)

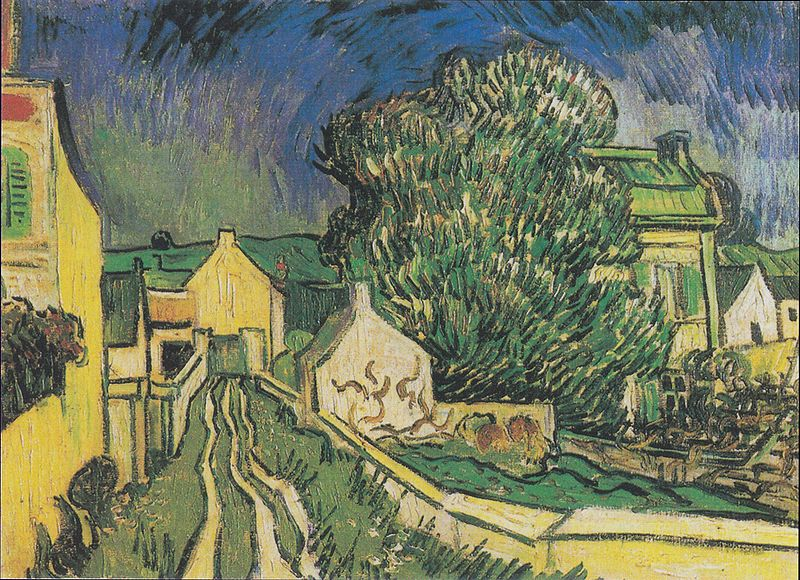

Vincent van Gogh ‘The House of Père Pilon’ (1890)

Vincent van Gogh ‘Marguerite Gachet in the Garden’ (1890)

Vincent van Gogh ‘Doctor Paul Gachet’ (1890)

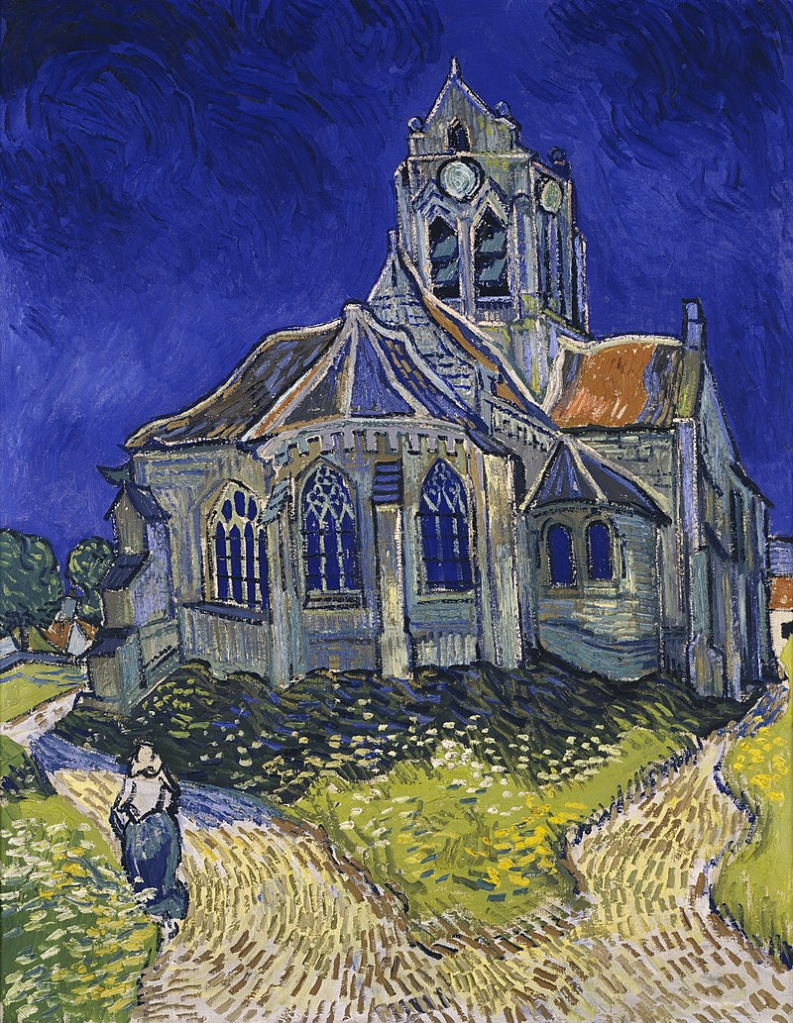

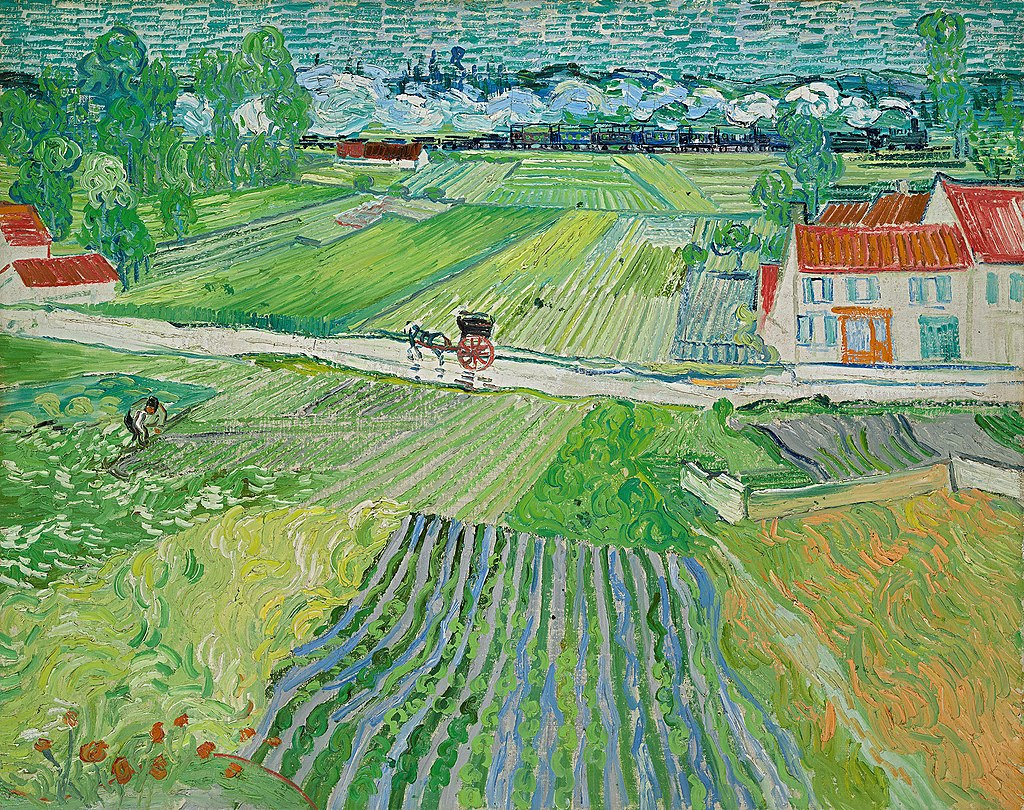

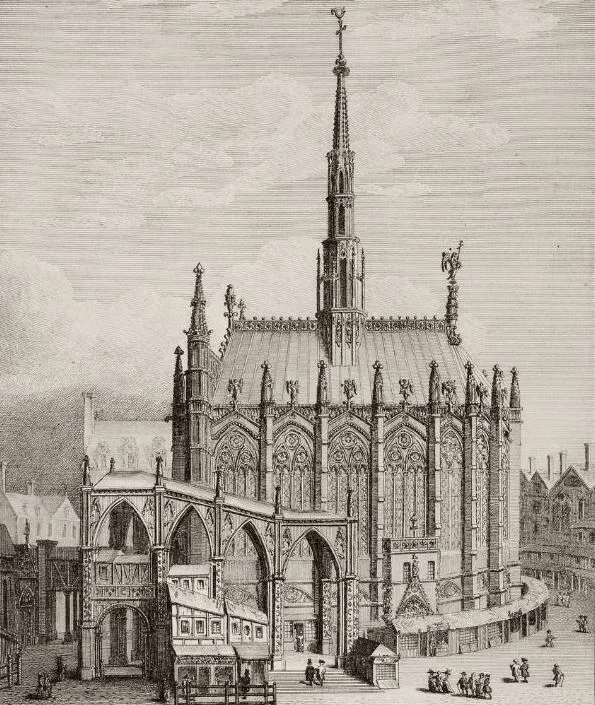

At the beginning of June he painted one of his best-known works from this period, ‘The Church at Auvers-sur-Oise’. He was clearly becoming happier at this time and on 10 June wrote to Theo, “It’s odd, all the same, that the nightmare should have ceased to such an extent here.” In one day, 12 June, he painted ‘Landscape with Carriage and Train’ and ‘Vineyards at Auvers-sur-Oise’.

Vincent van Gogh ‘The Church at Auvers-sur-Oise’ (1890)

Vincent van Gogh ‘Landscape with Carriage and Train’ (1890)

Vincent van Gogh ‘Vineyards at Auvers-sur-Oise’ (1890)

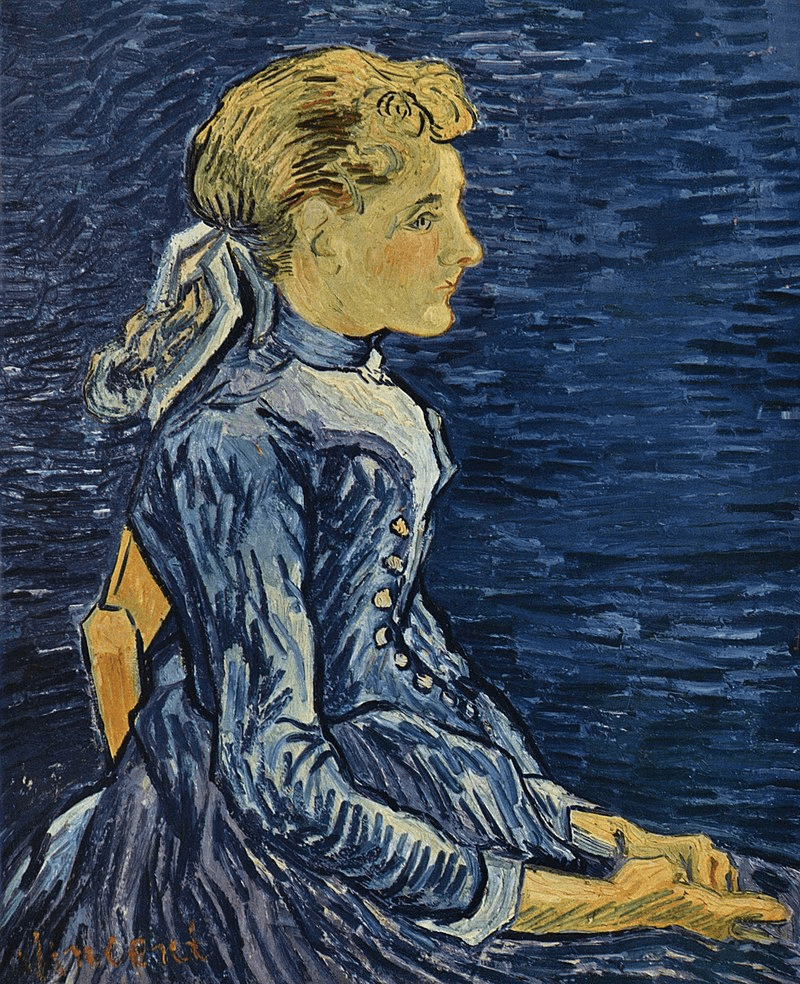

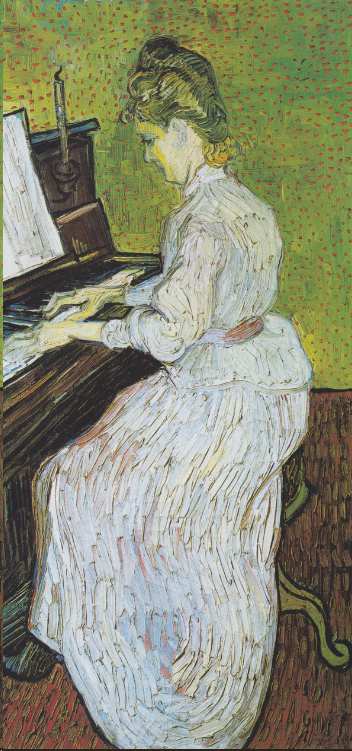

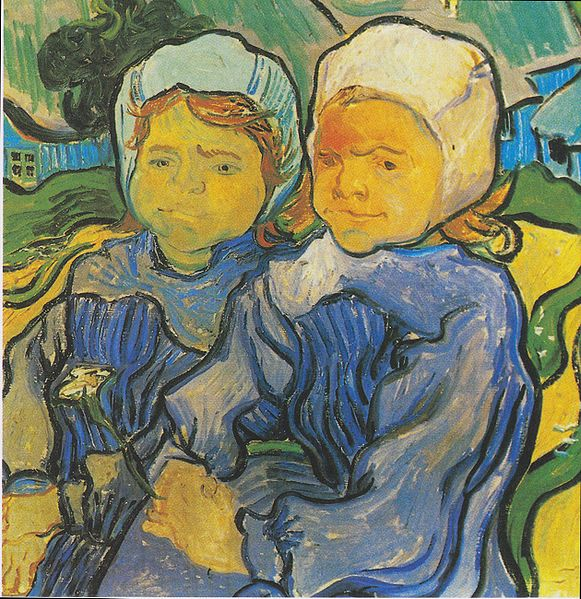

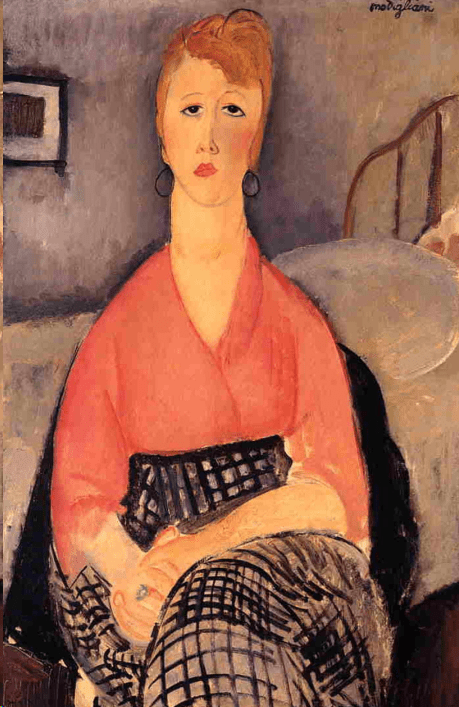

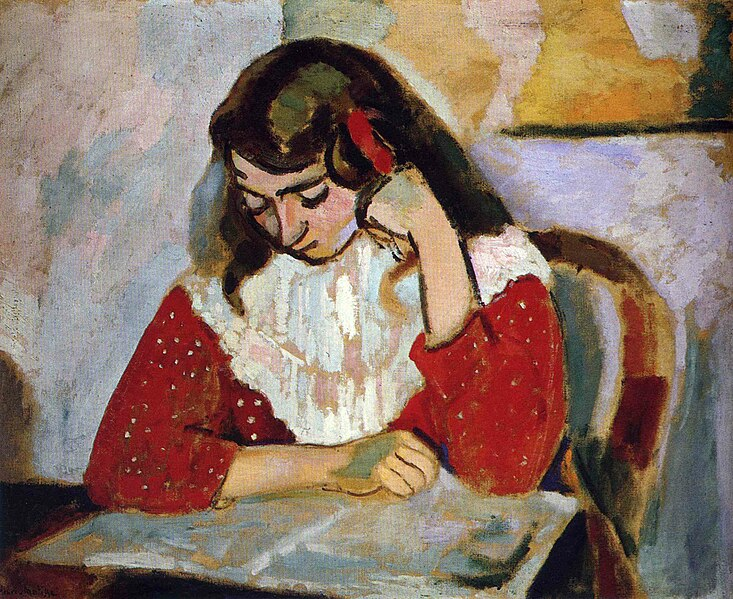

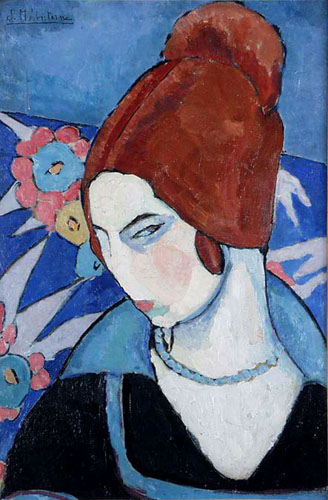

In June he also painted portraits, three of Adeline Ravoux, the daughter of the local inn-keeper, one of Marguerite Gachet at the piano, and several of local girls.

Vincent van Gogh ‘Portrait of Adeline Ravoux’ (1890)

Vincent van Gogh ‘Marguerite Gachet at the Piano’ (1890)

Vincent van Gogh ‘Two Girls’ (1890)

In early July he visited Theo and his family in Paris, although discussions there appear to have been quite fractious. Vincent also had fears about the health of both himself and Theo and his mood seems to have taken a downward turn. His final letter to Theo, written on 23 July but undelivered, was pessimistic, with Vincent declaring “I risk my life for my own work and my reason has half foundered in it.”

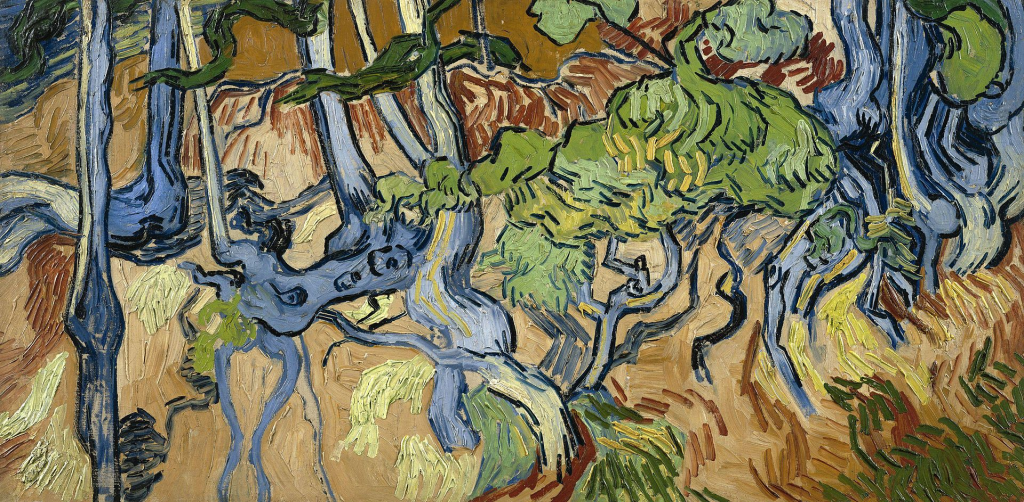

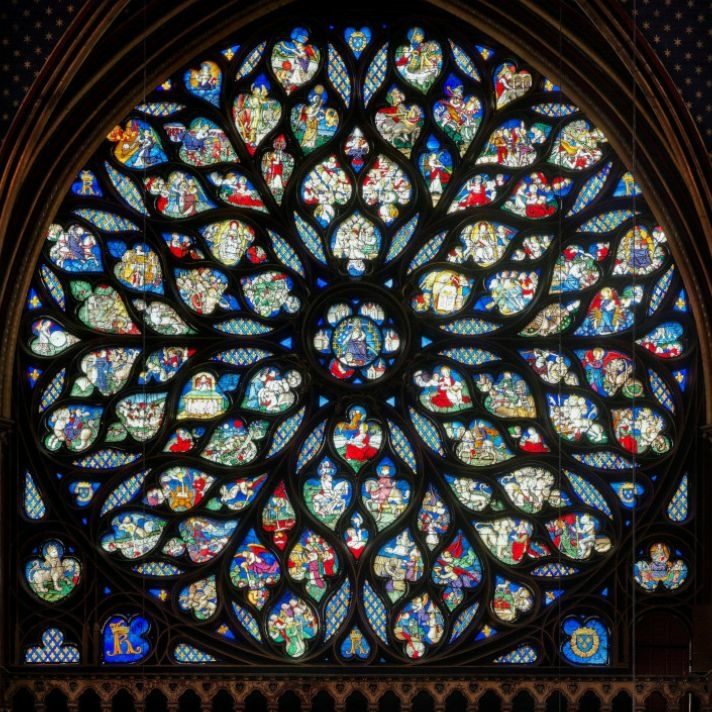

Vincent van Gogh ‘Tree Roots’ (1890)

On 27 July Vincent worked in the afternoon on his final painting, ‘Tree Roots’. That evening he shot himself in the area of the heart with a revolver and despite the efforts of Dr. Gachet to treat him he died at 1.30 a.m. on Tuesday 29 July. On 7 August, the local newspaper printed a short report which read: “Sunday 27 July, a person named Van Gogh, aged thirty-seven … Dutch citizen, painter by profession, living temporarily in Auvers, shot himself with a revolver in the fields and, being only wounded, returned to his room, where he died two days later.”