Whilst I have seen Renaud Capuçon play violin many times, I think this is the first time I have seen him as conductor and it was fascinating to witness his style. However, what made the programme of this concert so exciting is that in addition to works by Charlotte Sohy and Antonin Dvořák, Beethoven’s ‘Piano Concerto no.1’ was played by legendary pianist Martha Argerich, widely regarded as the greatest living pianist today.

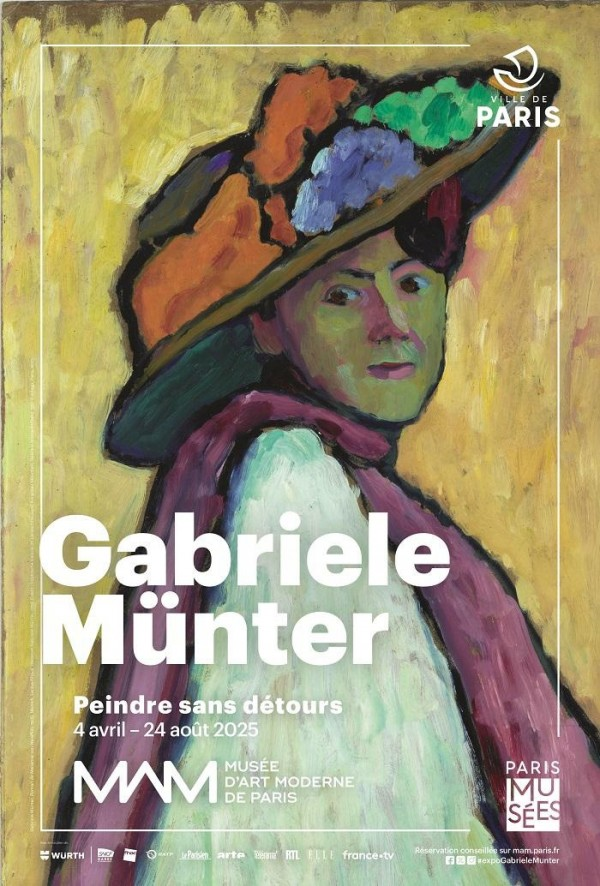

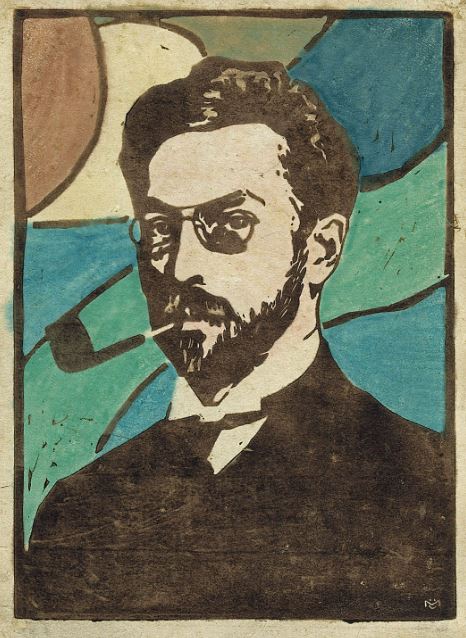

The evening began with Charlotte Sohy’s ‘Dance mystique’, which I had never heard before. Charlotte Sohy was born Charlotte Durey in Paris in 1887 into an affluent family and was introduced to the musical world at an early age, becoming friends with Nadia Boulanger. When she became a composer, aware of the obstacles faced by women in that profession, she used her grandfather Charles Sohy’s name as a pseudonym. She composed a symphony and other orchestral works as well as pieces for piano and string quartet. Her compositions were performed by Paul Dukas, Maurice Ravel and Gabriel Fauré.

‘Danse Mystique’ is an extremely original and rhythmic piece; a sacred, then almost euphoric dance to welcome the dawn. It is richly textured and quite mysterious in places and was played extremely well by the Orchestre Nationale Capitole Toulouse, providing a very pleasant start to the programme.

The first half continued with Beethoven’s ‘Piano Concerto no. 1’. It was written in 1795 and revised in 1800, and was actually completed after the second concerto, but it was the first to be published. There are still clearly Mozart and Haydn influences but Beethoven’s own unmistakeable voice is now emerging with adventurous harmonies and daring melodic ideas.

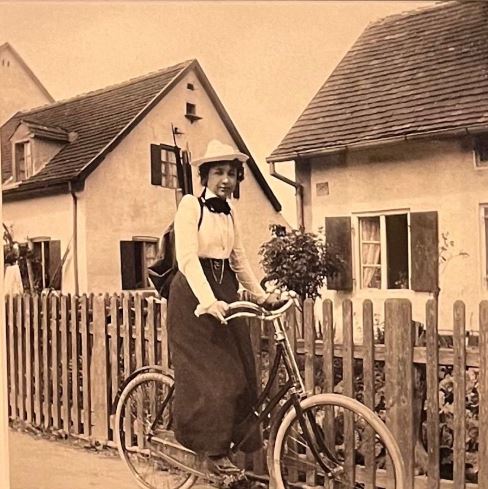

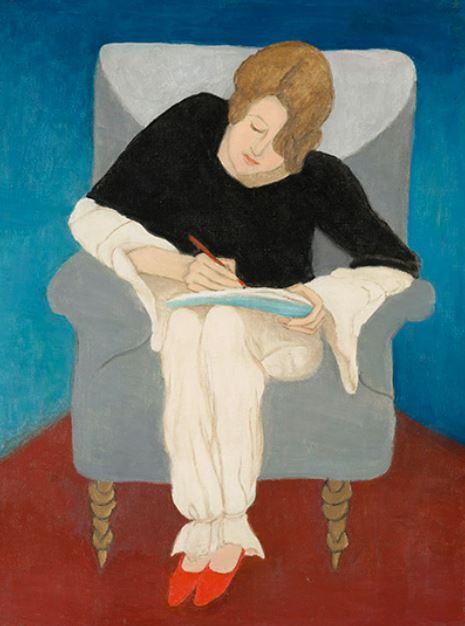

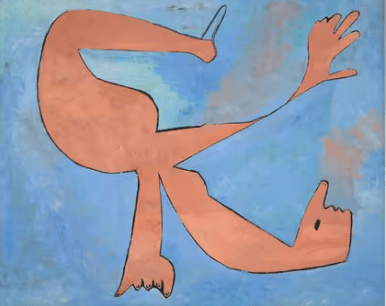

At only seven years old, Martha Argerich made her concert debut with Beethoven’s ‘Piano Concerto no. 1’ and she has continued to play the piece throughout her career, so it was a great thrill to see her perform it. It was played perfectly – the fast movements with an amazingly light but acrobatic touch and the slow movements with an intuitive grace and an elegant tempo. The Toulouse audience loved her and thunderous applause brought her back to the stage several times.

Martha Argerich

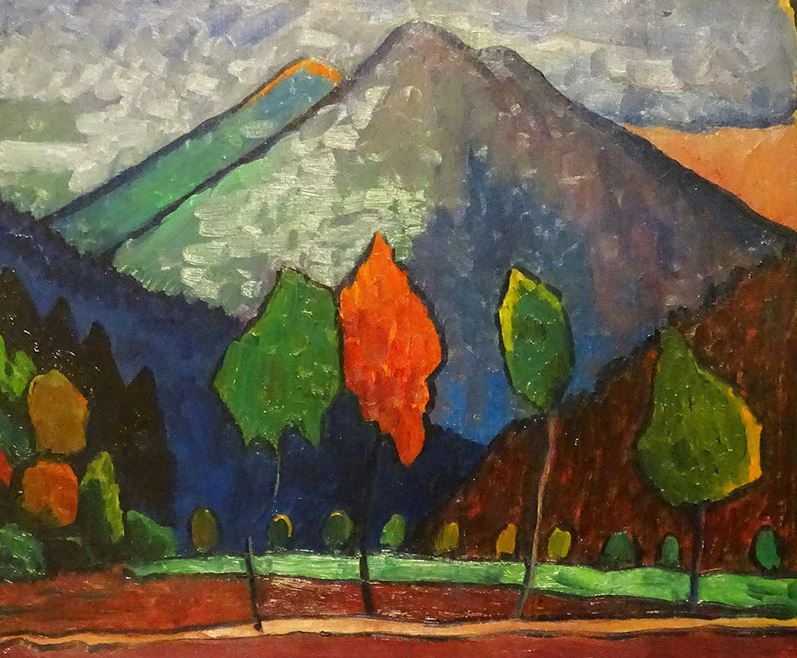

The second half of the concert was a performance of Antonín Dvořák’s ‘Symphony no. 8’. It was composed in 1889 on the occasion of his election to the Bohemian Academy of Science, Literature and Arts. Dvořák himself conducted the premiere in Prague in February 1890.

It is a very lyrical composition with a distinctly Czech flavour. The first movement is colourful and clearly draws on Bohemian folk melodies and I enjoyed the orchestra’s interpretation very much. The middle two movements are more pastoral with much dialogue between the woodwinds, the third being a waltz in 3/8 time. The fourth movement is much more turbulent, beginning with a fanfare of trumpets, the tension building throughout before it ends with a coda in which brass and timpani dominate.

This was a thoroughly enjoyable evening with the orchestra under Renaud Capuçon on form throughout, but it will be particularly remembered for the experience of seeing the extraordinary Martha Argerich perform so beautifully.

Charlotte Sohy: ‘Dance mystique’, opus 19; Ludwig van Beethoven: ‘Piano Concerto no. 1 in C major’, Op. 15; Antonín Dvořák: ‘Symphony no. 8 in G major’, Op. 88.